Agile development has some dirty secrets. By “dirty,” I mostly mean well-intentioned compromises we’ve all seen play out. The big one?

If your team finishes 100% of their planned work every single sprint, they are probably underperforming.

I know, that sounds like heresy. We are trained to love green checkmarks. Everyone wants “Burndown Charts” that actually burn down. We all want the dopamine hit of moving every ticket to “Done.”

But in my experience, an obsession with “completing the sprint” often leads to two dangerous behaviours:

- Sandbagging: Teams overestimate their estimates to ensure they never “fail,” resulting in a comfortable but slow pace.

- Burnout: Teams kill themselves to cross an arbitrary finish line by Friday afternoon, only to start Monday exhausted.

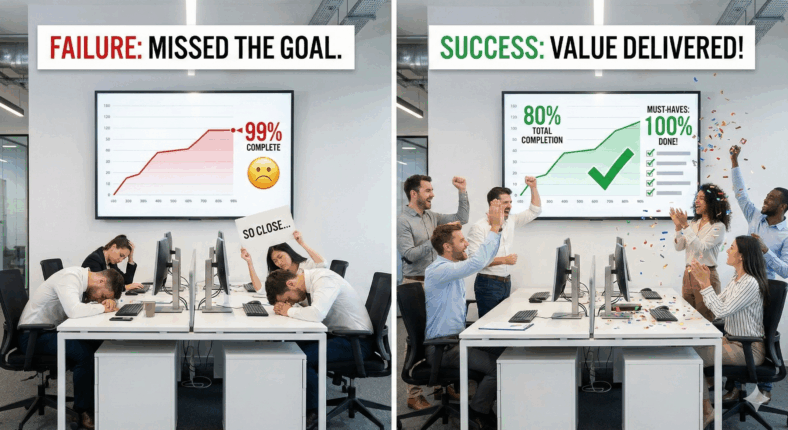

You need to reframe what “Success” looks like. It isn’t about doing everything; it’s about doing the right things.

The “Failed Sprint” Fallacy

I’ve seen teams demoralized because they carried over 3 points of work in a 40-point sprint. They treat it as a failure. Management asks, “Why didn’t you finish?”

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of what a Sprint is. A Sprint is a container for focus, not a blood oath.

As Mike Cohn from Mountain Goat Software wisely points out, if a team always finishes everything, they likely aren’t stretching themselves. They are playing it safe.

I encourage teams to stretch. I want them to aim high. But, and this is the critical part, they cannot be punished for missing that stretch goal. If you encourage ambition but punish the result, you will just get a culture of fear and padding.

Borrowing from “Shape Up”: Must-Haves vs. Nice-to-Haves

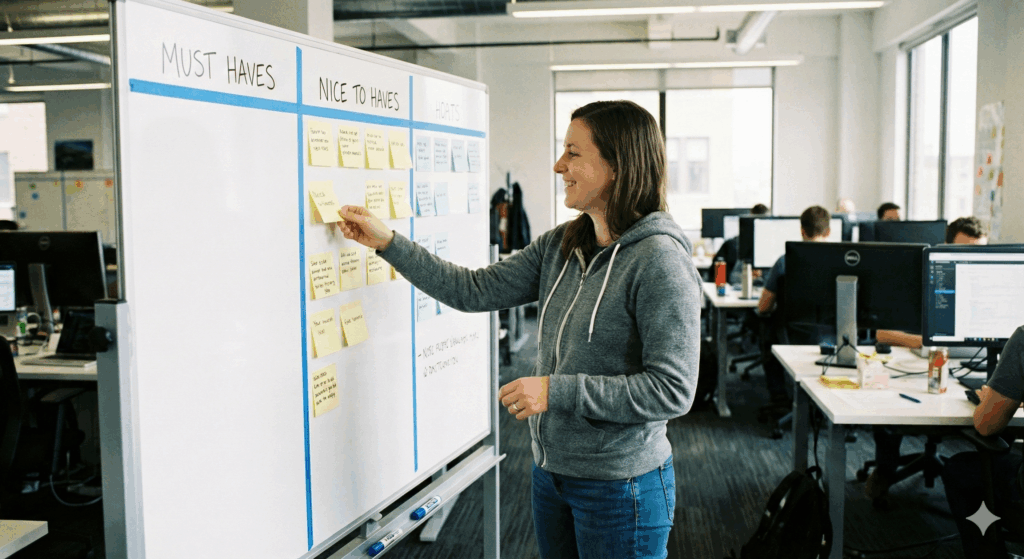

One way you can help your teams navigate this is by borrowing a concept from Basecamp’s Shape Up methodology and applying it to Agile processes.

In Shape Up, scopes are variable. You can apply this to Sprint Planning by categorising your backlog:

- Must Haves (The Core): These are the critical deliverables. If you don’t ship these, the sprint goal is missed.

- Nice to Haves (The Stretch): These are valuable, but if they slide to the next sprint, the world doesn’t end.

This subtle shift changes the psychology of the team. Instead of looking at a board of 20 tickets and thinking, “We have to do ALL of this or we fail,” they focus on the Core. Once the Core is secure, they attack the Stretch with confidence, not panic.

Capacity is Finite, Value is Infinite

As I wrote in my post on Story Points, estimates are just best guesses. We can’t predict the future, and we can’t magically create more hours in the week.

You can’t do everything, and that is okay.

A “Failed Sprint” isn’t one where tickets move to next week. A Failed Sprint is one where:

- The team burned out to hit an arbitrary deadline.

- They delivered low-quality work just to say it was “Done.”

- Despite delivering 100% of the work, none of it moved the needle for the customer.

Summary

As a leader, you need to stop asking, “Did you finish everything?” and start asking, “Did you deliver the most important thing?”

If the answer to the second question is Yes, then the sprint was a success—regardless of what the Jira chart says.

Further reading

If you enjoyed this post then be sure to check out my other posts on Engineering Leadership.

Join the flock

Subscribe to get the latest posts on the messy reality of software delivery sent directly to your mailbox. I regularly share new thoughts on leadership and strategy —zero spam, just value.

Leave a Reply